« Pure psychic automatism through which it is intended to express, either verbally or in writing, or in any other manner, the true functioning of thought. » André Breton, Surrealist Manifesto, “Éditions du Sagittaire”, 1924, Paris, France

The exhibition, curated by Didier Ottinger and Marie Sarré, to mark the centenary of Surrealism at the Centre Pompidou in Paris defies expectations, just like the movement it celebrates. As the French poet and Surrealist theorist André Breton declared in his Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), Surrealism cannot be understood rationally – it is an unbridled exploration of the subconscious that transcends logical boundaries. This guiding principle is palpable in the exhibition, which unfolds as an immersive labyrinth of artistic, literary and political provocations.

Running until January 13, 2025, this exhibition offers more than a retrospective; it is a daring recontextualization of Surrealism as a cultural phenomenon that continues to stimulate our imagination and push the conventional boundaries of art. It is a bold witness to Breton’s declaration that “beauty will be convulsive or not at all” (from his work Nadja, 1928), and seeks to revive the disruptive energy of the cultural phenomenon.

The exhibition opens with a striking reference to the origins of Surrealism: the original manuscript of André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism. This iconic document, which is being shown in its entirety for the first time thanks to a loan from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, takes center stage as a symbolic artifact of the movement. In 1924, Breton’s words called for a revolution in the perception of reality and became an appeal to the power of the unconscious in order to liberate the wild beast of the subconscious, thanks to the influence of Freud’s psychoanalytic analyses in the early 1920s..

It is not surprising that the representative image of the exhibition is the apocalyptic vision of the painting L’ange du foyer, also called Le Triomphe du surréalisme, by the German Max Ernst, which depicts a supernatural beast with anthropomorphic features, as if to capture simultaneously the two states of «dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality […]», as Breton wrote.

If the first rooms show the best-known and most recognized aspects of Surrealism, moving on we enter sections that certainly multiply and enrich the references of Surrealism, all of which are always accompanied by a rich documentary set, and here we get to the core of the 14 sections, named as follows: Entrance of the Medium, Trajectory of the Dream, Lautréamont, Chimeras, Alice, Political Monsters, Kingdom of Mothers, Mélusine, Forests, Philosopher’s Stone, Hymns to the Night, Tears of Eros, Cosmos; by luring the viewer into a realm where the boundaries between art, literature and psychology dissolve.

Forget the idea that surrealism is a curious relic of the past. This exhibition asks us to see it as a living, breathing forcethat is still pushing the boundaries of creativity and social critique. It’s not just about strange imagery or eccentric behavior; it’s about the power of the irrational to disrupt social norms. The exhibition explores Surrealism’s political engagement, its critique of colonialism and patriarchy and its quest for artistic freedom. It is an art movement that not only lived on the fringes of society, but also actively addressed the pressing social problems of its time — and still does, before our eyes.

Women Surrealists breaking boundaries

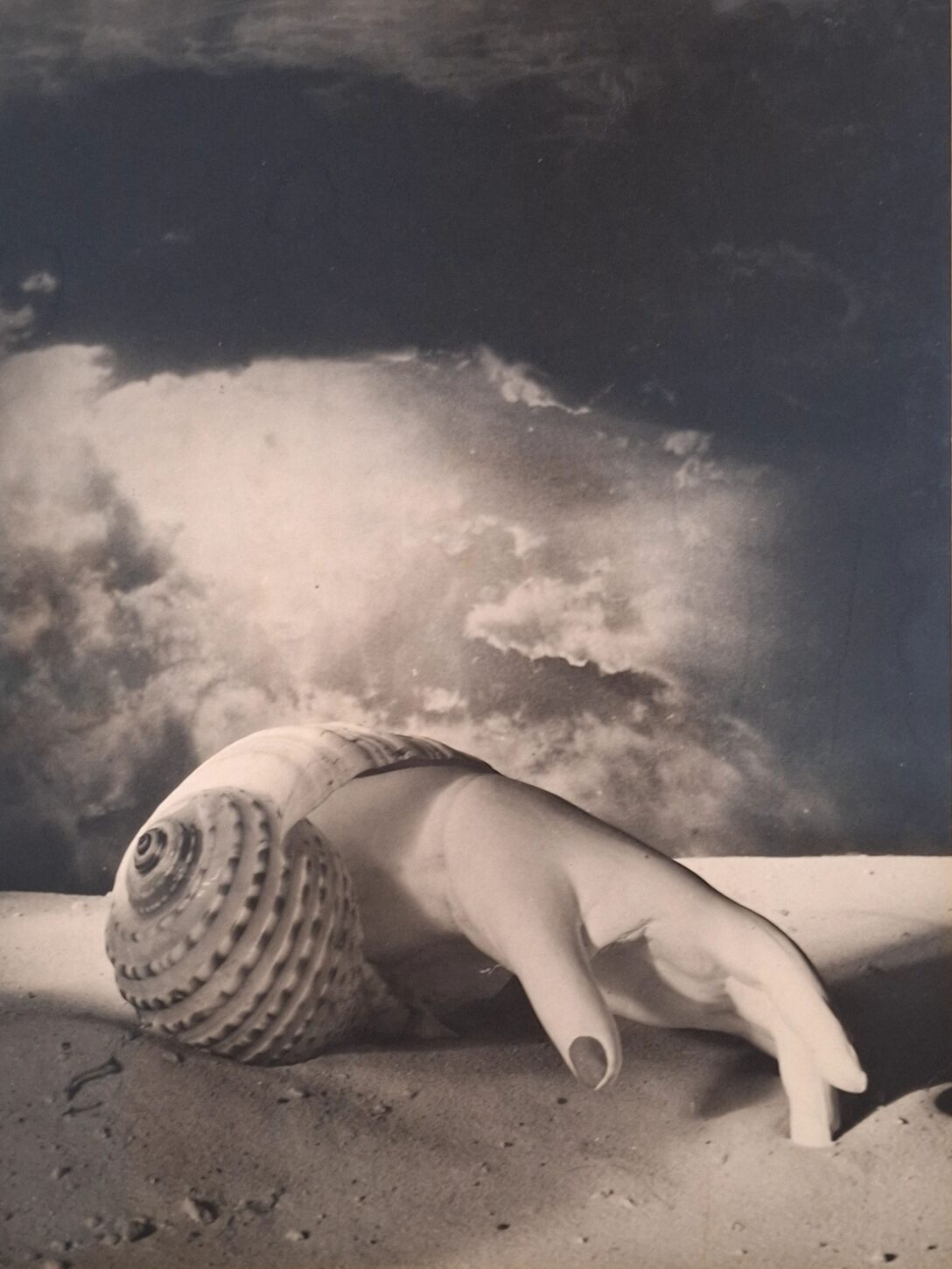

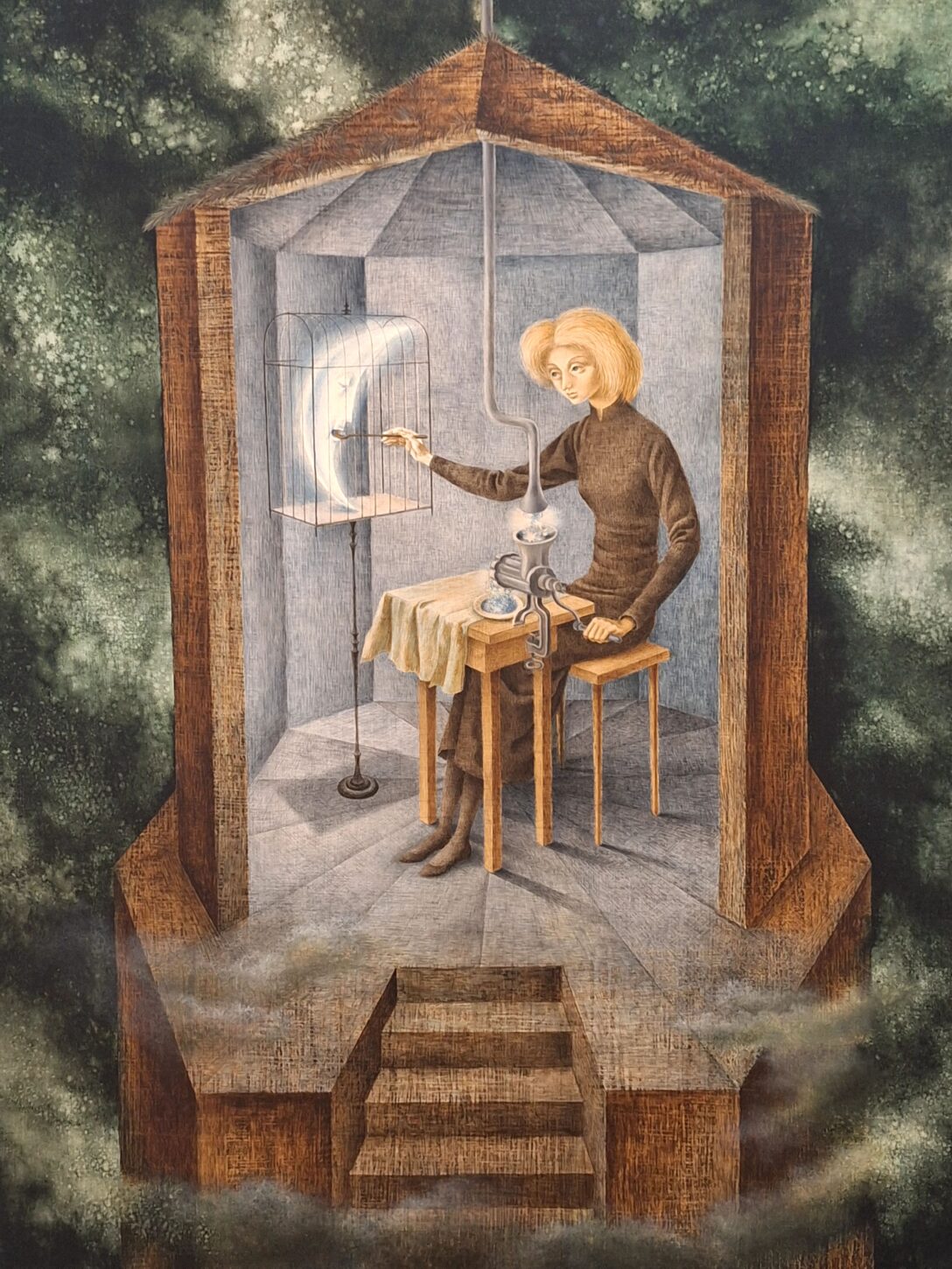

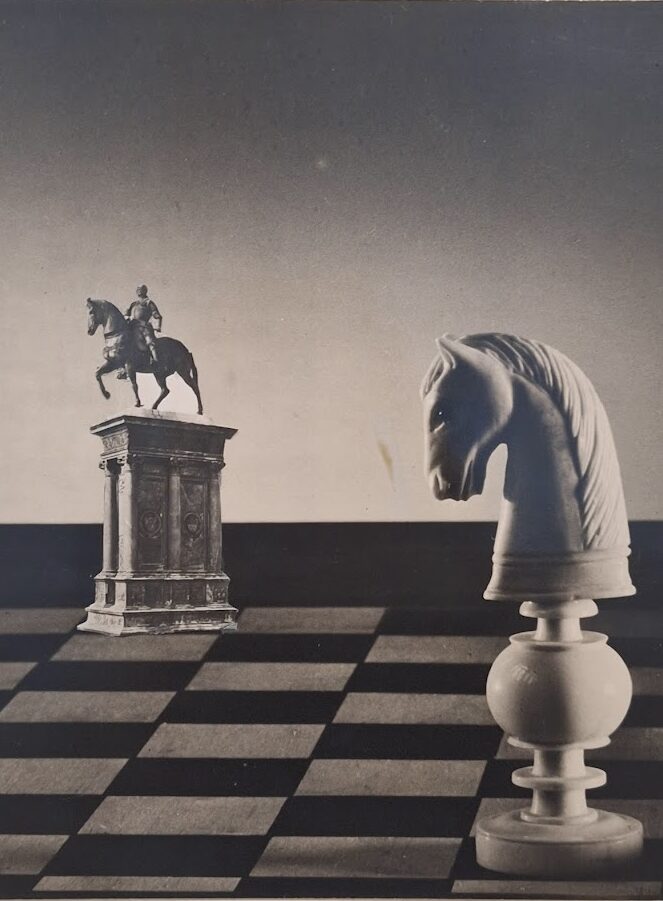

Expect to find Dalí, De Chirico, Mirò and Magritte’s pipes alongside works by the oft-overlooked female painters Dorothea Tanning, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Suzanne Van Damme, photographer Dora Maar and illustrator Valentine Hugo. A standout feature of the exhibition is, in fact, its focus on the contributions of women artists, challenging the traditionally male-centric narrative of Surrealism. By highlighting these figures, the exhibition not only honours their contributions, but also acknowledges their struggle for recognition in a male-dominated art world. Through this highlighting, the history of Surrealism is enriched by presenting it as a more inclusive and dynamic movement that benefited from the creative power of women artists who expanded its horizons in profound, personal and mythological ways, denying their role as muses or passive figures. Varo’s Celestial Pablum (1958), for example, transforms domestic imagery into a cosmic allegory, while Carrington’s dream-like visions question archetypal narratives with mystical intensity and Dora Maar’s photographs reveal a haunting interplay of reality and illusion.

A whirlwind journey that was not limited to France in the 1930s, but extended throughout Europe until the late 1960s, and thanks to these women also to the USA and Mexico, where the surrealist avant-garde (which merged its traits with the others, Dada and Futurism) had an almost spiritual revelation for Frida Kahlo, profoundly merging her personal vision with a symbolic, dreamlike visual language.

The exhibition not only shows what you already know, but also discovers hidden treasures that will make you rethink your ideas about Surrealism and its lasting legacy in all areas of art and culture. It’s a buffet of the bizarre, with works ranging from crazy paintings to experimental films, photographs, drawings and more. The exhibition’s innovative approach sets it apart from traditional retrospectives as it illuminates the many ramifications of Surrealism, exploring emotional, psychological and intellectual dimensions while reflecting the movement’s evolution from its literary origins to its profound influence on society.

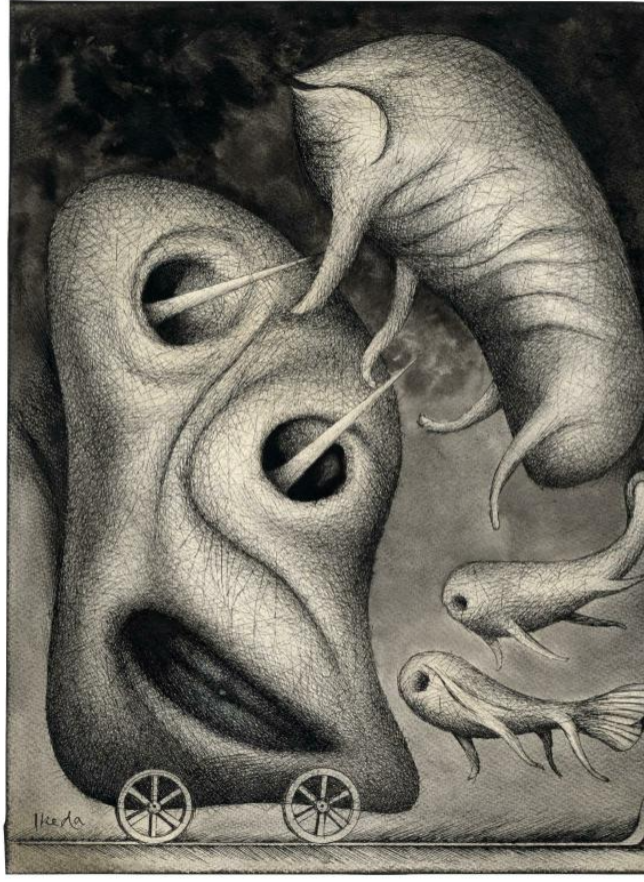

Beyond artistic experimentation, the exhibition highlights Surrealism’s radical engagement with political and social issues. Far from being an escape movement, Surrealism questioned colonialism, criticised patriarchal structures and understood creative freedom as an act of resistance. The global reach of the movement is evident in works from Latin America, Japan and beyond, showing how Surrealism’s challenge to rationality fell on fertile ground in different cultural contexts. This global influence is evident in works such as Victor Brauner’s “Loup-table” (1939) and Japanese artist Tatsuo Ikeda’s subversive explorations of power and oppression.

From Paris to the World: Surrealism Goes Global. This isn’t just a Parisian movement; it’s a worldwide revolution. The exhibition is unapologetically global, emphasizing how Surrealism’s critique of rationality and convention had an impact far beyond the boulevards of Paris. It’s clear that the dream logic of Surrealism wasn’t limited by geography – it found fertile ground in various cultures, sparking a universal artistic dialogue that continues to shape global art today.

In its audacious scope and intellectual rigor, the Centre Pompidou’s centennial celebration is not merely an exhibition but an invitation—to explore, to question, and to imagine. Far from a historical artifact, Surrealism emerges as a timeless call to liberation, creativity, and resistance to mechanized modernity and consumerism, a theme that resonates strongly in today’s world of environmental and social crises. In a world that increasingly feels like a waking dream, Surrealism continues to offer the perfect lens through which to make sense (or nonsense) of it all. It’s an invitation to rethink reality itself. “Perhaps life needs to be deciphered like a cryptogram”, as Breton wrote. And who can resist that?

On the cover: “L’ange du foyer” (Le Triomphe du surréalisme), 1937. Photo Adago Paris Vincent Everarts Photographie

Written by Sabrina Sabatino

Leave a Reply